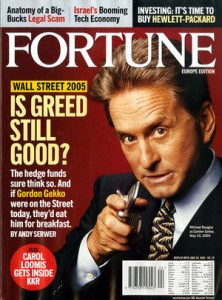

Cynicism is fashionable. But Gordon Gekko Was Wrong! Greed is Not Good!

Presidents, whether Republican or Democratic, always speak about Service, and when talking about wars, they speak of Sacrifice, and The Ultimate Sacrifice. Many approach their role from that perspective as well. George H. W. Bush, for example, approached politics from the traditional Conservative perspective of service. He also tried to spur volunteerism – the 1000 points of light.

But Reagan believed in Hoover’s fallacy, in the rugged individualist riding off into the sunset. What he didn’t understand is that those iconoclastic rugged individualists ride horses descended from wild beasts tamed thousands of years ago. Their horseshoes are made by blacksmiths. Their guns are made in factories. Their boots, clothes, and other gear are made in other workshops or factories. These rugged individualist, giants as they might be, stand on the shoulders of others.

You don’t teach kids to swim by pushing them off a pier. They don’t need flotation devices in 15 cm of water, either. What they need is someone to show them how, in waist deep water, and to say, “This is how it’s done. Why don’t you try? And don’t worry, I’ll make sure you don’t drown.”

The code of the Good Samaritan was simple: “Help when help is needed.”

Indeed, this is the common thread of 3000 years of human moral thinking, beginning with Abraham, Moses and Jesus in the West; Confucius and the Budda in the East.

Deborah Stone, in The Samaritan’s Dilemma, Should Government Help Your Neighbor? (C 2008, Nation Books, ISBN: 978-1568583549) shows that Gordon Gekko’s ethos, and that of Milton Friedman and Ronald Reagan, stems from Thomas Malthus and Ralph Waldo Emerson at their worst. While Friedman and Reagan ushered us into the contemporary world; Malthus, Emerson, and a fear of communism led Herbert Hoover to believe that market forces would end the Great Depression and private charity would alleviate suffering. He was wrong.

Deborah Stone, in The Samaritan’s Dilemma, Should Government Help Your Neighbor? (C 2008, Nation Books, ISBN: 978-1568583549) shows that Gordon Gekko’s ethos, and that of Milton Friedman and Ronald Reagan, stems from Thomas Malthus and Ralph Waldo Emerson at their worst. While Friedman and Reagan ushered us into the contemporary world; Malthus, Emerson, and a fear of communism led Herbert Hoover to believe that market forces would end the Great Depression and private charity would alleviate suffering. He was wrong.

Malthus’ real argument, according to Stone, is less a scientific treatise on population and hunger and more a political tract that suggests that helping the poor brings on more poverty. Emerson confuses bonds of community with bondage of servitude. It’s as if they read “A Modest Proposal” by Jonathan Swift, and thought he was serious.

Stone looks at where we are, how we got here, and where we need to go next. She outlines, and rebuts, “Seven Bad Arguments Against Help.” She discusses what she calls “everyday altruism” and “The Samaritan Rebellion.” The stories she relates can – and should – bring a tear to your eye – especially the accounts of the lives of people killed on September 11.

She shows that democracy is built on cooperation, and describes what might be called Hoover’s Fear, and America’s Folly, which is the path on which our government treads. “Unlike dictatorships and totalitarian forms of government, democracy requires citizens to participate in making laws and policies – to govern themselves.”

There’s altruism everywhere you look. Not just doctors, nurses, and teachers, but cops, firefighters, emergency workers. Stone concludes that while most people believe that everyday altruism, volunteerism, and community service are outside the sphere of politics, this faith that people have the capacity to make a difference is integral to democracy and personal fulfillment. “Done right,” she says, “government help strengthens democracy.” The New Deal and the Great Society grew out of a sense of justice and fairness to correct visible inequalities of wealth and power. Ronald Reagan’s Presidency and culture however, which has defined America from 1980 to the present, reverses the liberal, and liberating prescription. “Rather than power, and assertiveness, the poor need tough discipline, to listen to authority, and to be submissive.” After 30 years, it can be fairly established that Friedman’s neoMalthusian principles, Reagan’s beliefs, and Hoover’s fears have been America’s folly.

We need to take responsibility for our selves and our communities.

The details are below the click.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Mathus, Emerson, a fear of communism, and the mythic figure of a self-sufficient American cowboy riding off into the sunset led Herbert Hoover to believe that market forces would end the Depression and private charity would alleviate suffering. The election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932 proved him wrong. Friedman, Reagan and the same myths and fears ushered in the contemporary world. However, Malthus’ real argument, Stone says, is less a scientific treatise on population and hunger and more a political tract that suggests that helping the poor brings on more poverty.[1] Emerson confuses the bonds of community with bondage.[2] Had they read Jonathan Swift’s Modest Proposal

[3] they might have thought he was serious.

In Chapter 1, The American Malaise, Stone looks at where we are, how we got here. She outlines, and rebuts, “Seven Bad Arguments Against Help.” Then she discusses what she calls “everyday altruism” and the Samaritan Rebellion. She concludes with a discussion of what government and work should be all about:

- Jobs should pay a living wage,

- Jobs should allow workers to do their jobs and take care of their families,

- Government should supplement family care with publicly supported care.

These are Keynesian goals. Keynes, after all, said the goal of the economy is full employment. However, these were not the goals of Hoover, Reagan, Bush, or their economics gurus. We got here by forgetting Keynes.

As noted above, Stone is a political scientist. However, political science and economics are joined at the hip. Politicians must have a grasp on economics in order to define and implement good policy. Clinton’s famous mantra was “It’s the Economy.” As Stone wrote in her earlier book Policy Paradox,[4] “In order to do policy, you need to be good at politics.”

Where we Are

A cartoon in the New Yorker, in 1999, summed it up. A child asks his father for help with his homework. The man declines, saying, “Daddy will help you by not helping you.”

Government “of the people, by the people, and for the people,[5]” should be in tune with what de Tocqueville observed. Americans, he observed, have “an enlightened regard for themselves /which/ constantly prompts them to assist one another and inclines them willingly to sacrifice a portion of their time and property to the welfare of the state.”[6] Altruism and self-interest, Stone says, are “quite compatible, if not the same thing.”[7]

Stone distinguishes between what people expect from their neighbors – and expect to provide to their neighbors, and what they expect from politicians and the government. She finds people all over the country who give time and money to help others. Doctors, nurses, teachers, are paid for their work. Others, many others, volunteer. Some drive elderly people to physicians and hospitals. Others cook for friends, strangers, or countrymen. Some deliver Meals on Wheels. Others build homes in Habitat for Humanity. Still others volunteer in political campaigns.

But government and politicians are another matter. America in the 1960’s was filled with a postwar optimism. We defeated the Nazis, and we were going to the moon. Then things changed. Late in the 1970’s Milton Friedman and the Chicago School taught that unbridled pursuit of self-interest is the root of all things good. Economics and was overtaken by rational choice theorists. Their model citizen was a robot that knows only one thing: how to maximize its gains. It lives in a world of win-lose games in which helping others is a sign of weakness.

What might be called Hoover’s Fear or America’s Folly, is the path on which our government has tread since 1980. The irony is that while the neocon philosophers, from Ayn Rand to Friedman and the rest view the Soviet Union as the pinacle of altruism, the Soviet and Chinese Communist systems have produced the most cynical self-centered and cut-throat people on the planet, surpassing even Wall Street. “Unlike dictatorships and totalitarian forms of government,” Stone says, “democracy requires citizens to participate in making laws and policies – to govern themselves.”[8] Our democracy is, as Lincoln observed, “Government of the people, by the people, for the people.”[9]

Neuroscience, she reports , trumps [classical and neoclassical] economics. What we percieve in others we feel in ourselves. Altruism has been scientifically measured to be self-reinforcing. When we help someone we both benefit. We can see this in any interaction between people and infants. If you smile at a baby, the baby smiles back. When a baby smiles at an adult or a bigger child, the other person smiles back. This is not only limited to humans. When someone pets a cat they both purr. People with dogs are always talking to other people, with and without dogs, on their walks. “They exude happiness,” my son said, about the dolphins he swam with on vacation.

Stone outlines – and rebuts – “Seven Bad Arguments Against Help.”

- Help makes people dependent. Humans are born dependant. We may teach ourselves how walk. But all else, talking, reading, thinking, is from our teachers. Education makes people productive.

- Entitlements undermine good citizenship. Stone says this argument is essentially that “seeking help is really wrong. Help makes people look to others rather than taking responsibility for solving their own problems. People who are down and out neither need nor deserve help.” Stone observes that people who argue against Affirmative Action rarely argue against “legacy” enrollments in prestigious colleges.

- Help robs people of freedom and dignity. No one wants to need help. However, when help empowers people without subordinating or demoralizing them it gives people voice, leverage, and dignity.

- Help enslaves the helpers. We are the government. We know when we are young, that we will need help when we are old.

- When there’s not enough for everyone, we can’t afford to be generous. This is Malthus and Darwin speaking thru neocons. Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932 said “our distress comes from no failure of substance. . . . Nature still offers her bounty and human efforts have multiplied it. Plenty is at our doorstep but generous use of it languishes in the very sight of supply.”

- People are compassionate for their own good. Stone’s argument here is simple. “Robert Frost defined a home as ‘When you have to go there, they have to take you in.’ If we want a home where they have to take us in, we must also make a home where we have to take them in.”

- Markets are better helpers than government. Markets may be good at providing STUFF, but they are not good at ensuring that everyone can get the Stuff they need. And there’s more to life than stuff.

Everyday Altruism

Then Stone talks about everyday altruism. There are obviously altruistic professions: teachers, doctors, nurses. “I get more than I give” is their constant refrain, and the key. Just because they are paid, doesn’t negate the help they provide. There are other things that they could do. There is also an element of altruism in police and firefighters. Boy Scouts are taught to run out of burning buildings. Firefighters run in to get people out. They do it for the good of the community. And some die, that others may live. An element of altruism motivates members of the armed forces. When Presidents, whether Republicans or Democrats, speak of soldiers, they talk of sacrifice, and supreme sacrifice.

The stories she relates can – and should – bring a tear to your eye, especially the accounts of the lives of people who were killed on September 11 and who volunteered to help others. Stephen Dimino, Colleen Deloughery, Abe Zelmanowitz, Telmo Alvear, Olabisi Shadie Layenyi-Yee, Brian Warner, Brian Monaghan, Benjamin Suarez, Keith Glascoe, Sandra Campbell, others. Some made tremendous sums at Cantor Fitzgerald, others made modest livings as waiters. The New York Times published their obituaries every day for three months as “Portraits of Grief.” In this, as Stone reminds us, “the Times broke with its tradition of formal obituaries for people of fame and achievement. Instead, we saw ordinary people who led lives of dignity, hope, love, and kindness. We learned what they valued about their lives, and what their loved ones cherished about them. It wasn’t self-reliance. It wasn’t the pursuit of self-interest with a breezy faith that an invisible hand or divine justice would take care of everyone else. . . . . These people loved their families. They were kind. They were always ready to help someone else.”[10]

Chuck Sereika, a former medic, put on his old uniform and went down there to help. He ordered oxygen and an IV for one of the trapped men. . . . he could hear the rumble of 4 World Trade Center, but kept on working.” He had struggled with alcoholism for years, been in and out of rehabilitation, spent a few nights in jail, lost jobs and friends, but on Sept. 11 . . . “It’s very easy for me to help people. It comes naturally to me and to all paramedics. It’s what we do. Taking care of myself, I’m not so good at.” [11]

Altruism and Community Service IS Government

Stone concludes that while most people believe that everyday altruism, volunteerism, and community service are outside the sphere of politics, this faith that people have the capacity to make a difference is integral to democracy and personal fulfillment. “Done right,” she says, “government help strengthens democracy.”[12] The New Deal and the Great Society grew out of a sense of justice and fairness to correct visible inequalities of wealth and power. Ronald Reagan’s Presidency and culture however, which has defined America from 1980 to the present, reverses the liberal, and liberating prescription. “Rather than power, and assertiveness, the poor need tough discipline, to listen to authority, and to be submissive.” After 30 years, it can be fairly established that Freidman’s neoMalthusianism, Reagan’s beliefs, and Hoover’s fears have been America’s folly.

We need to take responsibility for our selves and our communities. And as noted above, she concludes with a discussion of what government and work should be all about:

- Jobs should pay a living wage,

- Jobs should allow workers to do their jobs and take care of their families,

- Government should supplement family care with publicly supported care.

It’s a persuasive argument. Where I think The Samaritan’s Dilemma might be lacking is that Stone, and her readers, need to be able to speak to independent voters and thinking conservatives as well as progressives. We need to understand how to frame the issues. On the other hand, George Lakoff has done that. Read The Samaritan’s Dilemma

alongside Lakoff’s Don’t Think Of An Elephant, Moral Politics, and Thinking Points.

[1] Deborah Stone, The Samaritan’s Dilemma, 2008, Nation Books, New York, Pg 69-74.

[2] Ibid Pg 25-26.

[3] Jonathan Swift, A Modest Proposal, 1729, on the Internet at Art-Bin.com, http://art-bin.com/art/omodest.html

[4] Deborah Stone, Policy Paradox, The Art of Political Decision Making, Revised, 2001, W. W. Norton & Company.

[5] Abraham Lincoln, Address at Gettysburg, Delivered Nov. 19, 1863.

[6] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 2 Vols, 1835 and 1840, reprint New York, Vintage Books, 1990, vol 2, book 2, p 122.

[7] Deborah Stone, Pg 92.

[8] Stone, Pg 201.

[9] Aberaham Lincoln, Address At Gettysburg, reproduced by American Constitution Society for Law and Policy, ACSLaw.org.

[10] Stone, Pg 16-17.

[11] Stone, pg 31.

[12] Stone, Pg 245.