The Centers for Disease Control, CDC, on May 3, 2012 issued a brief but unequivocal statement regarding the health implications of hydraulic fracturing here, and reproduced in it’s entirety below.

CDC / ATSDR Hydraulic Fracturing Statement:

CDC and ATSDR do not have enough information to say with certainty whether natural gas extraction and production activities including hydraulic fracturing pose a threat to public health. We believe that further study is warranted to fully understand potential public health impacts.

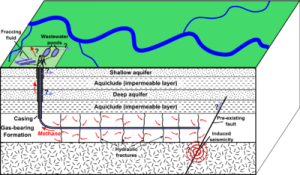

The CDC, in its 47-word statement said, “We don’t know the public health implications of hydraulic fracturing, aka ‘fracking’ or ‘frakking.’ We need to study the issue.” Perhaps the decision makers at the CDC should watch Gasland. But consider the CDC statement on hydraulic fracturing in light of picture 2 and the “Precautionary Principle,”

The precautionary principle or precautionary approach states that if an action or policy has a suspected risk of causing harm to the public or to the environment, in the absence of scientific consensus that the action or policy is harmful, the burden of proof that it is not harmful falls on those taking the action.

The Precautionary Principle is described in more detail on Commonweal (here) and Science & Environmental Health Network, SEHN (here). Burning fuel for heat requires obtaining the fuel and releases various materials into the biosphere. We must understand the consequences and side-effects before we embark on any project. The questions in re hydraulic fracturing are:

- Are these pictures real or imagined?

- What are the implications for the water supply and the biosphere?

- What are the liability insurance requirements? and

- What are the alternatives?

This argument is similar in structure to Pascal’s wager, in which Pascal argued that in the absence proof of God’s existence, one should behave as though God exists and live a moral and ethical life. If God is found out later to have existed, and assuming God rewards good works and punishes evil, the post-life consequences are good; if God does not exist, no harm can be sustained after death.

Pascal’s wager is also described at the Stanford University Encyclopedia of Philosophy, here, at the UTM Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, here, and at SecularWeb, aka Infidels.org, here.

With respect to hydraulic fracturing, the Precautionary Principle isn’t difficult to apply: if “fracking” goes badly, here are some of the consequences:

- Contamination of the water table; because fracking involves lateral pressures which may meet resistance from geological formations, and rearranging underground gas and oil worst-case outcomes include fouling of the water table at relatively great distances – certainly distant from the leased properties; seismic shifts, risk releases of oil and gas into water tables, and shifts in the landscape;

- these undesirable effects, if and when they occur, may affect many people and wide geographic ranges, which suggest that (a) many such bad outcomes which might have to do with fracking may require litigation and very expensive fact-finding in order to to establish claims; (b) if presumed effects present themselves in dispersed patterns, the cost of investigation and proof may mean that legitimate claims don’t come to the attention to the courts;

- Like the asbestos cases which have become a substantial public health and judicial problem, actual damages and discovery of those damages may not occur for many years;

- We don’t know a lot about the effects of current fracking technologies.

So the CDC’s expression of concern and endorsement of research – all well and good. There is no question that more information is needed. The question is whether or not a prudent society or a prudent government would want that information – the question is whether or not testing and research come before proceeding with hydraulic fracturing, a more cautious approach, or whether we go ahead – and passively note the risk and find out what happens, if anything, after it happens.

We could, for instance, do small-scale trials in conjunction with widely spaced data gathering which would permit us to more precisely assess the risk. The energy shortfall(s) in the meantime can be covered with a combination of aggressive energy-efficiency measures, and investments in renewable resources. Here is the other side of the Precautionary Principle:if fracking turns out to be entirely without risk, we’ll still have those underground resources to exploit, we’ll need less energy (conservation), and we’ll have more available (renewable resources). So if and when the perfectly-safe “fracked” hydrocarbon fuel products hit the market, these other measures will still provide downward pressure on prices, and place less stress on the ecosystem.

This is the first in a planned series on hydraulic fracturing. Additional posts will explore the long term ramifications including the insurance limits and questions of liability.