Bob Garfield began the segment, Assessing the True Threat of Cyberwar, on the WNYC radio show On the Media, on Friday, August 10, 2012,

Last year when a water pump in Springfield, Illinois burned out, a water district employee noticed that the system had been accessed remotely from somewhere inside Russia. Two days later, a memo leaked from the Illinois Intelligence Fusion Center, made up of state police, members of the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security, blamed the pump failure on Russian hackers. It looked to be the first example on American soil of the worst case scenario in cyber warfare, that a hacker could wreak havoc in the physical world.

Eireann Leverett, a security researcher at IO Active describing using Shodan to estimate the scope of what’s connected to the Internet:

[I]n spite of the danger it posed, [I] found more than 12,000 industrial control systems, the kind of systems that control critical infrastructure, connected to the public internet. But how, exactly, did he do it?

Amazingly, Leverett told me that when he had a hard time even starting this project. When he tried to scan for these pieces of infrastructure on the internet, the very act of scanning would cause the computers to crash. Luckily for Leverett, there was SHODAN.

SHODAN (named by its creator, John Matherly, for the rogue artificial intelligence in the video game Deus Ex System Shock) is like Google for computers. It allows users to search for computers, routers, webcams, smart phones, anything that is directly connected to the internet. Leverett used it to map what are called SCADA systems – systems control industrial equipment, which can mean everything from milking machines to power plants.

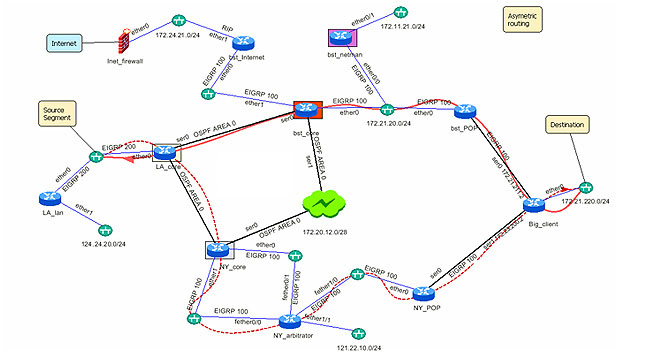

As noted here, in our posts on network vulnerability, Paul Baran, the early Internet theorist, pictured at left, posited that corrupt – let’s say “hijacked” – nodes on a network had to be severable from their networks. Baran’s insights about network robustness and resilience are no less relevant today than they were when he wrote for the Air Force and DOD at the RAND Corporation in the 1960’s.

As noted here, in our posts on network vulnerability, Paul Baran, the early Internet theorist, pictured at left, posited that corrupt – let’s say “hijacked” – nodes on a network had to be severable from their networks. Baran’s insights about network robustness and resilience are no less relevant today than they were when he wrote for the Air Force and DOD at the RAND Corporation in the 1960’s.

But certain networks should, perhaps, not just be severable – but be independent networks, or perhaps not networked at all. For instance, a telephone system which is not dependent on the local power utility means that power outages (absent, say, an ice storm which knocks out both power and phone lines at once) don’t knock out communications systems.

Renewable power sources – solar and wind, for instance – can be wired into the power grid, but pre-set to disengage from the power grid during outages, so as to serve local critical infrastructure – hospitals being a good example. Is there a compelling case for having a network where someone either clever or reckless could find a single node from which to remotely turn off power at hospitals? Of course not. There are such people, in the categories of malicious, reckless and merely negligent. If they’re to turn the power off at hospitals, shouldn’t we raise the bar at least high enough that they can’t manage it all in one stop? Let’s at least force people to attack us one target at a time, and let’s make it hard.

Another discussion of Cyberwarfare on Popular Logistics includes Larry Furman’s piece about cyber-crime, cyber-espionage, and cyber warfare in Cyberwar: USA & Israel v Iran, China v USA, Russia v The World on July 1, 2012.