There aren’t enough bees to perform all of the pollination work in the United States. So, if you like to travel, make money doing it, and don’t mind a sting now and again, then professional beekeeping may just be for you. And hey – it’s a seller’s market.

About 1.4 million hives get hauled to and around California every spring. They travel by plane, semi or pickup trucks. 60% of the American hives are engaged in commercial pollination. They pollinate almond trees, and other key crops:

- Cranberries in Massachusetts and New Jersey.

- Blueberries and peaches from Jersey to Georgia,

- Pumpkins from Jersey to Illinois.

- If it comes from a flowering plant, it’s pollinated by bees.

You can take your bees “On The Road” and make money without writing a word. And if you actually hate to travel, you can just send the bees.

Just make sure they all don’t all disappear.

Jeff Anderson, a Minnesotan beekeeper with forty years experience, started 2012 with 3,015 beehives. That fall, as was his wont, he rented out most his stock to California growers to be set up in almond groves. It’s a mild climate for bees to over-winter – it sure beats Minnesota – and not only do the bees make a nice revenue in rental fees, they come home to Minnesota heavier with honey, which Jeff harvests in the late summer. There are not enough bees to meet pollination demands, nor are there enough gallons of honey to meet consumer demands, so Jeff Anderson has got his feet in two seller’s markets. How tough is that?

Except, one year later, – 2013 – he started with just 992 colonies, most “in severely weakened condition,” following their sojourn from California. At best a 67% loss, but more realistically something like an 85% loss, as the surviving hives had depleted populations and were no longer commercially viable. One semi that went out to California from Jeff’s apiary left with 480 hives, only 150 came back alive. There was no clear indication what had happened to the bees – mainly because the bees didn’t die in the hive, leaving behind bodies which can be examined. It’s as if the worker bees had flown off, abandoning the colony. Of late, the malady has been called Colony Collapse Disorder, or CCD for short. Anderson spent most of 2013 in recovery mode. He went political and became the moving spirit behind a few bee-keeping political action committees. More on that in a later post.

With forty years of experience, Jeff Anderson is not a newbie. He knows about Varroa mites and Nosema and takes steps to minimize their impact. A professional, he can recognize their tell-tale signs and understands the root cause. He does not rent out compromised hives, which might die off in transit. Nor is it that the people he does business with are wet behind the ears. Growers know that when it comes to bees, it’s a seller’s game, so they are careful with insecticides. Ditto with the shippers who move bees from place to place; it’s a premium shipping market if you have a reputation for delivering bees alive. Otherwise it’s the DHL short-hauls for you, buddy.

In short, everyone in the 2012-2013 season doing business with Jeff were seasoned professionals who knew their businesses. In this setting, Jeff Anderson could expect hive losses around 10% to 20%, dying off from causes that he knows about and can identify. That’s how it stacked up in the previous years. Jeff Anderson expected that the 2012/13 season would more or less stack up the same way.

It didn’t. Nor was it clear to Anderson why the die-offs happened. Some hives did receive pesticide exposure, some did have mites, and Anderson could identify these. But many hives were just vacated, bees gone, no bodies, but with the physical signs of bee health and prosperity still present — honey stores and brood, bees and pupae still in the honey comb, and no particular indication that grower carelessness or shipper clumsiness figured as root causes. It’s just that hives which went out healthy in November came back empty or nearly so. and at percentages way outside the norm for such things.

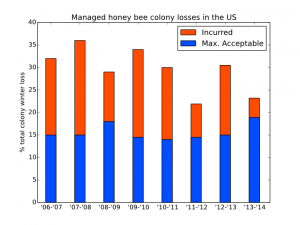

Blue: “acceptable” loss rate built into the business model. Red: actual total losses. Source: beeinformed.org Winter Surveys

If what had happened to Jeff Anderson was an outlier, the statistical bolt-from-the-blue, nobody outside of Jeff and his immediate family would have cared much.

Unfortunately, what happened to Jeff is becoming more and more common. According to the USDA, average colony losses experienced by beekeepers has been around 33% for the years 2006-2011, up from an average loss of 15% for most of the 1990’s.

The annual Winter Survey which beeinformed.org has maintained since 2006 tells a similar story (see graphic). This survey concentrates on the September — April time period when the Northern Hemisphere winter stresses bee colonies and the highest rates of colony demise occur. Canvassing about 20% of US beekeepers annually, about 7,000 operators in 2013-14, the survey asks about the percentage of total losses, the ratio of hives dying over the winter months to live hives at the start of September, plus hive splits made over the period. The graphic depicts this ratio in red. The survey also asks beekeepers about the loss rate factored into their businesses, the maximum they can sustain and still turn a profit. That percentage, in blue, has been constantly outstripped by actual loss rates over the entire time the Winter Survey has been conducted.

It takes about $500.00 to restart a dead hive, which will be too small for the initial season to be very profitable. Average losses of 33% are hard to carry year in and year out. For an operator like Jeff Anderson, 33% is about a thousand hives, with replacement costs around $500,000, not including the cost of carry for about one season before such hives return on investment. For a majority of beekeepers, losses of more than 50% are impossible to sustain after a year or two. The loss rate of 30% – 33%, the norm over the last eight years, is simply inducing beekeepers to quit the business.

Presently, bee-keeping is a declining business, despite being a seller’s market in multiple sectors. The 2.6 million commercial hives available to growers in this decade are down from the 5 million that had been available to their fathers and grandfathers in the 1940’s or the 4.5 million hives that were still available in the mid 1980’s.

So, even without colony collapse disorder, bee-keeping has grown riskier. The Varroa mite infestation of bee colonies began in the U. S. in the 1990’s and is still growing. No longer can a beekeeper assume that an established colony will just keep on growing, splitting into two, four, eight, sixteen, thirty-two… hives. Implosions like what happened to Jeff Anderson are no longer improbable, and could become likely in the next decade.

Next: Colony Collapse Disorder