The Constitution tasks the House of Representatives with setting the number of U. S. citizens that its members may represent. The Apportionment Act of 1792 fixed the House of Representatives for the Third Congress at 105 members, one Representative for 33,000 constituents. The Census of 1790, first of its kind, found the young nation numbering around 3,900,000 individuals. For purposes of computing the ratio of representatives to those represented, slaves constituted three-fifths of a free person.

112 years on, 1901, roughly midway between the Constitution’s ratification and the present day, each Representative of the 57th Congress fielded the concerns of 213,000 people and carried a six-fold increase in “representational load” over his 1792 counterpart. The House then had 357 members representing around 76 million. Had the House stayed with its 1792 ratio of one Representative to 33,000 constituents, it would have had 2,303 members in 1901, far more than what the seating in the south wing of the Capitol building could accommodate.

114 years on, the 114th Congress finds a House of 435 voting members, a number which has been fixed since the Apportionment Act of 1911. These worthies now represent about 309 million, or roughly 710,000 citizens per Representative, a four-fold increase over the 1901 representational load and a twenty-four fold increase over that of 1792. At the original ratio, the House would have almost 9,364 members, a number making for a mad house – though some think it is anyway.

To this already tenuous connection among Representatives and Those Represented there arises a further dissipative force, the fine art of gerrymandering. The textbook ideal that Congressional districts are uniform in character, simply shaped perimeters constituting some fair regional cross-sections of opinions, trends, interests and habits, fixed in population so that each equals all others but is of otherwise neutral political character, is something that could not be left untouched for long in the struggles for political advantage. Alas, the fine art of shaping Congressional districts so that they might have some distinct political orientation is as nearly as old as the Federal Constitution itself.

Gerrymandering is a portmanteau of Elbridge Gerry, in 1812 the Governor of Massachusetts and the first known practitioner of the art, and “salamander”, the shape of that inoffensive creature being most like that of the Congressional district which Gov. Gerry had created, at least in the minds of Massachusetts Federalists. Gerry, a Democratic-Republican, was held in imperfect esteem by Federalists. The word, coined by a Federalist editor whose name has been lost to Antiquity, refers to both the process and the product, so those who draw Congressional districts both gerrymander and create gerrymanders. In the early Nineteenth Century, the word began with a hard ‘G’, but changed by the Twentieth Century to a soft ‘G’. Lately, some Twenty-first century pundits spell it like ‘perrymander’, in honor of a recent Texan Governor who exhibited advanced artistry in such skills.

State Legislatures practice the art in thirty three states. In seven other states the art is moot because there is nothing to draw, the state populations being so low as to forego Congressional districts. The ten remaining states, including some of the most populous in the nation, have – to varying degrees – removed the responsibility from the various state legislatures, placing it into the hands of “independent, non-partisan commissions.” The authorities of such commissions are final in six states but conditional on the approval of State Legislatures and/or Governors in four others. It is a matter of debate whether such commissions rise above gerrymandering or merely furnish another venue in which to practice it.

Whoever practices it, gerrymandering serves its practitioners in two, seemingly contradictory ways. The first is to pack a Congressional district with citizens of a particular political orientation. That may seem like a boon for its supporters; they will most overwhelmingly elect a Representative of their particular ilk to Congress. Alas! The artful concentration of particular voters into a particular district concomitantly depletes neighboring districts of that point of view, and these neighboring districts will, by design, be of greater number than the single district where the concentration was effected. These neighboring districts will likely go the other way and, overall, more Representatives of the opposite viewpoint will go to Congress. Voters in the packed district may sense that the effect of their votes have been diminished. If only they could have been in the neighboring districts, where they once were, and where wins of the opposition by whisker-widths could have been tilted the other way!

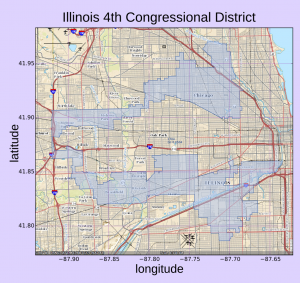

The 4th Congressional District of Illinois, winding its way through various Chicago neighborhoods.

The second is to crack voters into separate Congressional Districts, robbing voters possessing a particular point of view of winning in any Congressional district in the state, for they have been made, by artifice, a minority everywhere in the state. Cracking, as noted already, tends to run a counter course to packing. So where the dominant party of one political season sees an advantage to packing, the next runs to cracking, and vice-versa. In either case, the shapes of Congressional districts fall increasingly out of round. For example, the current 4th Congressional District of Illinois snakes through various suburbs around Chicago, and for a mile or so, between Elmhurst and Bellwood, it is no wider than Interstate 294, which it follows without incorporating any households on either side of the road. Voters in that particular part of the district tend to be hit by cars anyway, limiting their participation in the Great National Discourse.

It so happens that in this discourse, every political party professes a hatred of gerrymandering. But every party does it, because, of course, the other party has already done it, and so it must be undone – a Mexican stand-off. Thus, year after year, districts are re-drawn to crack the packing, or pack the cracking, nominally to “fix” the politicking done by the previous party but in practice to serve the political exigencies of the next Congress.

And politicking, pure and simple, is what gerrymandering is all about. It adds nothing to political discourse; it is pure political tactic. As the start of this post has noted, there is already a vanishingly small and tenuous act of representation between the Representative and the Represented. At a ratio of one to nearly three quarters of a million, anything that injects noise into such a delicately composed signal should be banned as being in the disinterest of the people.

Since every party professes to hate it, and yet all participate in it, the question arises as to how best to break the stand-off over gerrymandering. At present, this writer is entertaining the notion of a measure, a non-partisan, unitless indicator that stems from the intrinsic shape of the Congressional district itself. The writer calls this measure a Gerrymander Index and the method of its computation will be the subject of the next post.