On Dec. 21, 2012, I put $16 Million imaginary dollars in equal imaginary investments in 16 real energy companies; $8.0 in the Sustainable Energy space and $8.0 in the fossil fuel space. Excluding the value of dividends and transaction costs, but including the bankruptcy or crash of three companies in the sustainable energy space,

On Dec. 21, 2012, I put $16 Million imaginary dollars in equal imaginary investments in 16 real energy companies; $8.0 in the Sustainable Energy space and $8.0 in the fossil fuel space. Excluding the value of dividends and transaction costs, but including the bankruptcy or crash of three companies in the sustainable energy space,

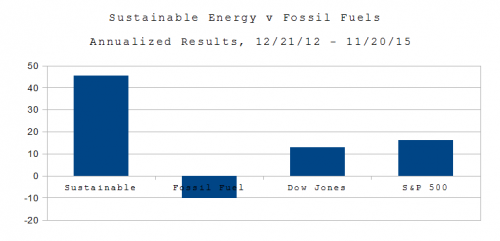

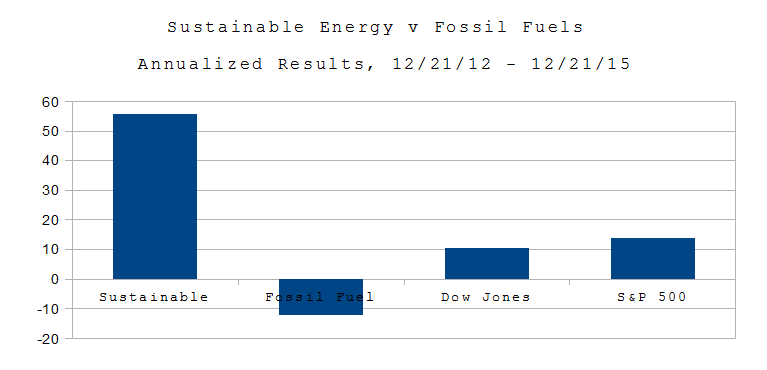

As of the close of trading on November 20, 2015:

- The Fossil Fuel portfolio was worth $5.63 Million, down 29.57% overall, down 10.44% on an annualized basis.

- The Sustainable Energy portfolio was worth $18.0 Million, up 129.50%, overall and 45.71% on an annualized basis.

- The Dow Jones Industrial Average is up 36.15% overall and 10.44% on an annualized basis, from 13,091 on 12/21/12 to close at 17,824 on 10/21/15.

- The S&P 500 is up 46.10% overall and 16.27% on an annualized basis, from 1,430 on 12/21/12 to close at 2,089 on 10/21/15.

It’s not a war on coal. It’s a paradigm shift.Think about it. We don’t use whale oil or kerosene for street lamps. We did, 100 years ago.

This of course, has geopolitical ramifications. It’s not just carbon dioxide, which is changing the climate and acidifying the oceans. Like Al Queda, Hamas and Hezbollah, ISIS finances its operations with petrodollars. (The difference is that Hamas is supported by Emirates and Kuwait, Hezbollah by Iran, Al Queda by our friends the Saudis, while ISIS has its own oil wells.) Earlier this year NJ’s Honorable Governor Chris Christie, a candidate for President, gave Exxon a $9 Billion gift (which is being challenged in the courts). BP was the beneficiary of the 1953 coup by the US under President Eisenhower and the UK which toppled the democratically elected government led by Prime Minister Mohammed Mossagedgh of Iran and propped up the Shah until the revolution in 1979. Shell has spent something like $12 Billion in failed attempts to drill the Arctic. BP, Transocean and Halliburton brought us the Deepwater Horizon; Halliburton also profited from the US Led war in Iraq.

Continue reading →

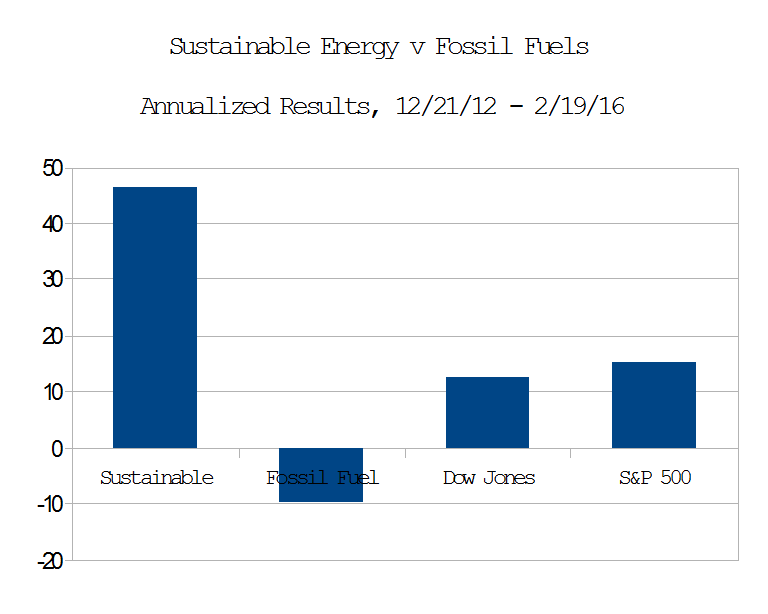

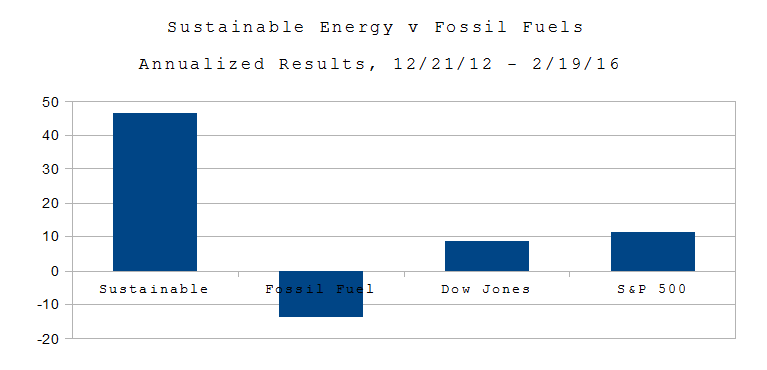

On Dec. 21, 2012, I put $16 Million imaginary dollars in equal imaginary investments in 16 real energy companies; $8.0 in the Sustainable Energy space and $8.0 in the fossil fuel space. Excluding the value of dividends and transaction costs, but including the bankruptcy or crash of three companies in the sustainable energy space, and one company in the fossil fuel space.

On Dec. 21, 2012, I put $16 Million imaginary dollars in equal imaginary investments in 16 real energy companies; $8.0 in the Sustainable Energy space and $8.0 in the fossil fuel space. Excluding the value of dividends and transaction costs, but including the bankruptcy or crash of three companies in the sustainable energy space, and one company in the fossil fuel space.

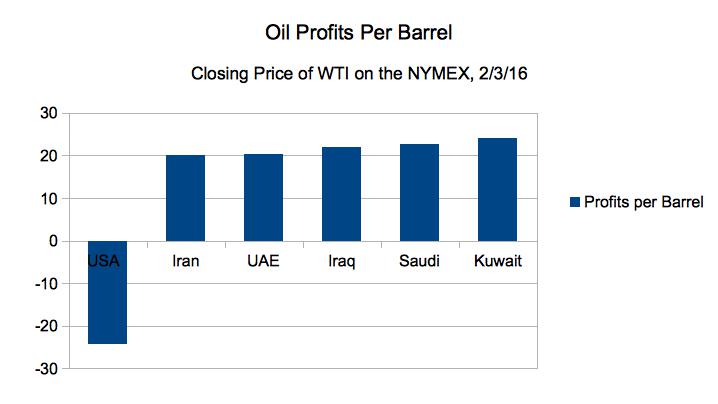

Deepwater Drilling Offshore of the US yields oil at $57 per barrel (see

Deepwater Drilling Offshore of the US yields oil at $57 per barrel (see

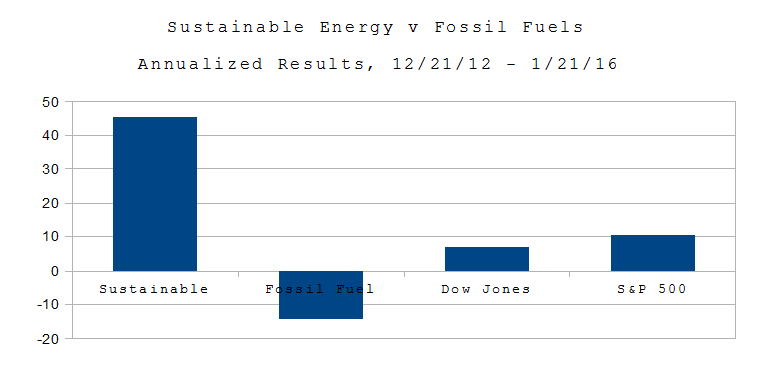

Wall St. 1/21/16. On Dec. 21, 2012, I put $16 Million imaginary dollars in equal imaginary investments in 16 real energy companies; $8.0 in the Sustainable Energy space and $8.0 in the fossil fuel space.

Wall St. 1/21/16. On Dec. 21, 2012, I put $16 Million imaginary dollars in equal imaginary investments in 16 real energy companies; $8.0 in the Sustainable Energy space and $8.0 in the fossil fuel space.

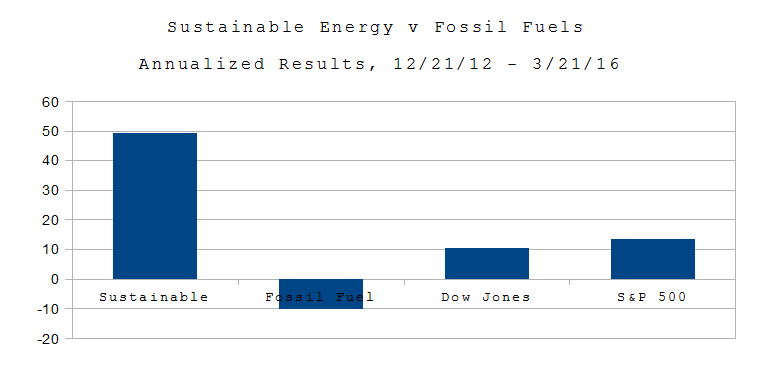

On Dec. 21, 2012, I put $16 Million imaginary dollars in equal imaginary investments in 16 real energy companies; $8.0 in the Sustainable Energy space and $8.0 in the fossil fuel space. Excluding the value of dividends and transaction costs, but including the bankruptcy or crash of three companies in the sustainable energy space.

On Dec. 21, 2012, I put $16 Million imaginary dollars in equal imaginary investments in 16 real energy companies; $8.0 in the Sustainable Energy space and $8.0 in the fossil fuel space. Excluding the value of dividends and transaction costs, but including the bankruptcy or crash of three companies in the sustainable energy space.