Third in a series (1, 2, 3) that began on “Earth Day” (0).

BP and the government say they can’t measure the spill on the ocean floor. However, 5,000 barrels per day is reaching the surface and most of the oil – 80% to 90% – is below the surface. So I thnk it’s is on the order of 25,000 to 50,000 barrels per day.

But that’s my back-of-the-envelope estimate. NPR, on Friday, May 14, 2010 reported that Steven Wereley, who teaches mechanical engineering at Purdue University, Tim Crone, a research scientist at Lamont-Doherty, and Eugene Chiang, an astrophysicist at UC Berkeley, believe they can make a pretty reasonable estimate of the amount of oil gushing into the Gulf. Wereley based his estimate on particle image velocimetry analysis of the video BP released. He says says 70,000 barrels per day, give or take 14,000 barrels, is gushing from the Deepwater Horizon spill. Crone agrees with Wereley but said he’d like better video from BP before drawing a firm conclusion. Chiang estimates the flow at 20,000 to 100,000 barrels per day. 880,000 to 2,200,000 gallons of petroleum products into the Gulf of Mexico Each

DAY! That’s 6,160,000 to 15,400,000 gallons per week.

After 20 days that’s 400,000 to 2.0 million barrels. Each barrel could have been refined into 44 gallons of gasoline, jet fuel, and other petrochemicals. But even at 5,000 barrels per day – 100,000 barrels in the first 20 days – this is a catastrophic event.

One hundred years from now, when historians, in energy efficient homes and offices powered by wind, solar, and geothermal, write about the end of the era of fossil fuel, they will point to the April 5, 2010 disaster at the Upper Big Branch, W. Virginia coal mine and the April 20, 2010 catastrophe at the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico.

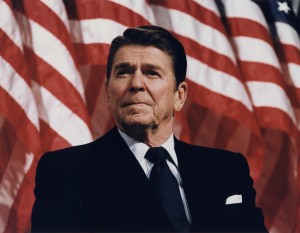

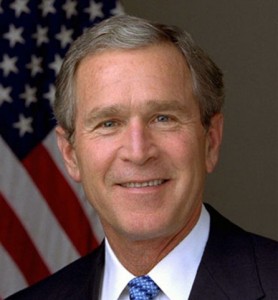

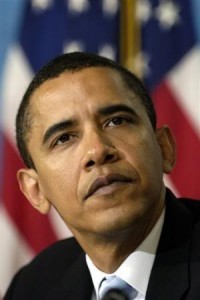

Historians may assign responsibility to the energy policies of President George W. Bush and Vice President Cheney. They will note that President Carter put solar water heating system on the roof of the White House (click here for pdf) and President Reagan took them down in 1986. Their assessment of President Obama will be predicated on his next actions. Does he continue to embrace “Drill Baby Oops,” Coal with Carbon Sequestration, and Nuclear Power? Or do a 180 degree turn to sustainability?

I don’t know what the pressures are at a depth of 5000 feet below the surface of the ocean. But there’s methane ice down there. At atmospheric pressure, Liquid Methane freezes is at -182.5 °C and methane gas liquifies at -181 °C (here)

The most important questions are:

What will be the effect of all that oil on fishing, tourism, the weather and the climate? It could be good for the maple syrup, solar power, and wind power industries, and the locavore food movement.

Given the severity of the spill, and what it demonstrates about our ability to operate at 5,000 feet below the surface of the ocean, I think we should rethink the Purgen Coal with Carbon Sequestration Plant, which will pump carbon dioxide into a well a mile below the ocean.

In addition, NPR reported on May 12, (here) that a House investigative subcommittee said Wednesday that the blowout preventer, had multiple defects — everything from leaky hydraulics to a dead battery.

How did it happen? BP and Transocean say the rig was built to handle working pressures of 20,000 PSI, but the safety equipment was built for pressures of 60,000 PSI. Clearly, the upward pressure released by drilling 18,000 feet below the ocean floor, itself at a depth of 5,000 feet below sea level, exceeded the 60,000 PSI – that’s 60,000 pounds per square inch. In terms of reference, atmospheric pressure at sea level is 14 PSI. For more information and an exploration of this, Click Here to “Moore Think, Less Confusion.

Full text of both articles by NPR are reproduced below the fold

Gulf Oil Spill May Far Exceed Official Estimates

The amount of oil spilling into the Gulf of Mexico may be at least 10 times the size of official estimates, according to an exclusive analysis conducted for NPR.

At NPR’s request, experts examined video that BP released Wednesday. Their findings suggest the BP spill is already far larger than the 1989 Exxon Valdez accident in Alaska, which spilled at least 250,000 barrels of oil.

BP has said repeatedly that there is no reliable way to measure the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico by looking at the oil gushing out of the pipe. But scientists say there are actually many proven techniques for doing just that.

Steven Wereley, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Purdue University, analyzed videotape of the seafloor gusher using a technique called particle image velocimetry.

A computer program simply tracks particles and calculates how fast they are moving. Wereley put the BP video of the gusher into his computer. He made a few simple calculations and came up with an astonishing value for the rate of the oil spill: 70,000 barrels a day — much higher than the official estimate of 5,000 barrels a day.

The method is accurate to a degree of plus or minus 20 percent.

Given that uncertainty, the amount of material spewing from the pipe could range from 56,000 barrels to 84,000 barrels a day. It is important to note that it’s not all oil. The short video BP released starts out with a shot of methane, but at the end it seems to be mostly oil.

“There’s potentially some fluctuation back and forth between methane and oil,” Wereley said.

But assuming that the lion’s share of the material coming out of the pipe is oil, Wereley’s calculations show that the official estimates are too low.

“We’re talking more than a factor-of-10 difference between what I calculate and the number that’s being thrown around,” he said.

At least two other calculations support him.

Timothy Crone, an associate research scientist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, used another well-accepted method to calculate fluid flows. Crone arrived at a similar figure, but he said he’d like better video from BP before drawing a firm conclusion.

Eugene Chiang, a professor of astrophysics at the University of California, Berkeley, also got a similar answer, using just pencil and paper.

Without even having a sense of scale from the BP video, he correctly deduced that the diameter of the pipe was about 20 inches. And though his calculation is less precise than Wereley’s, it is in the same ballpark.

“I would peg it at around 20,000 to 100,000 barrels per day,” he said.

Chiang called the current estimate of 5,000 barrels a day “almost certainly incorrect.”

Given this flow rate, it seems this is a spill of unprecedented proportions in U.S. waters.

“It would just take a few days, at most a week, for it to exceed the Exxon Valdez’s record,” Chiang said.

BP disputed these figures.

“We’ve said all along that there’s no way to estimate the flow coming out of the pipe accurately,” said Bill Salvin, a BP spokesman.

Instead, BP prefers to rely on measurements of oil on the sea surface made by the Coast Guard and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Those are also contentious. Salvin also says these analyses should not assume that the oil is spewing from the 21-inch pipe, called a riser, shown in the video.

“The drill pipe, from which the oil is rising, is actually a 9-inch pipe that rests within the riser,” Slavin said.

But Wereley says that fact doesn’t skew his calculation. And though scientists say they hope BP will eventually release more video and information so they can refine their estimates, what they have now is good enough.

“It’s possible to get a pretty decent number by looking at the video,” Wereley said.

This new, much larger number suggests that capturing — and cleaning up — this oil may be a much bigger challenge than anyone has let on.

Historians may assign responsibility to the energy policies of President George W. Bush and Vice President Richard B. Cheney.

Investigators Find Slew of Problems At Oil Rig

by NPR Staff and Wires

May 12, 2010

A House investigative subcommittee said Wednesday that the blowout preventer, one of the prime suspects in the Gulf of Mexico oil spill, had multiple defects — everything from leaky hydraulics to a dead battery.

The new disclosures revealed a complicated cascade of deep-sea equipment failures and procedural problems in the oil rig explosion and massive spill that is still fouling the waters of the Gulf of Mexico and threatening industries and wildlife near the coast and onshore.

The disclosures were described in internal corporate documents, marked confidential but provided to a House committee by BP, the well’s operator, and by the manufacturer of the safety device. Congressional investigators released them.

The April 20 BP rig explosion killed 11 people. Since then, nearly 4 million barrels of oil have spewed from the broken well pipe 5,000 feet underwater, 40 miles off the Louisiana coast.

The hearing gave the most complete picture yet of the blowout preventer and its actual condition.

“The safety of its entire operations rested on the performance of a leaking, modified, defective blowout preventer,” said Rep. Bart Stupak (D-MI), chairman of the House subcommittee that held the hearing.

One of the problems cited by the committee was already well-known: The blowout preventer’s blind shear ram, which is supposed to cut through the pipe and crimp it, can’t actually cut all the way through if certain sections of drill pipe are in the way.

There were other problems, too:

— A loose hydraulic fitting was letting fluid leak out.

— The blowout preventer had been modified, and one of the changes effectively crippled one of its five components.

— A piece of test equipment had been substituted for a ram that could have helped to stanch the flow of oil.

The modifications didn’t have good record, either.

After the blowout, engineers couldn’t figure out why robots weren’t able to make the undersea control panel work correctly. Another control pod didn’t work because it had a dead battery. Stupak said that led to the disabling of an emergency backup, called a deadman switch.

Subcommittee members pressed executives from BP, Transocean, which owns the rig, and Halliburton, which did cement work on the well.

Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-IL) repeatedly asked Transocean CEO Steve Newman if anyone made a mistake regarding the condition of the blowout preventer.

“It would be a mistake to rely on that in a well-controlled situation, yes,” Newman acknowledged.

“These measures are well within the means of science; this is not a new and unproven area, and if they’re not doing it, I hate to say it but it seems they’re choosing not to do it,” said Ian MacDonald, a professor of oceanography at Florida State University.

BP did release video from the seafloor on Wednesday but said it wants its workers to focus on stopping the flow.

Environmental Impact

Meanwhile, globs of oil were washing ashore at the mouth of the Mississippi River.

The water around Port Eads, a lighthouse that’s at the southernmost tip of Louisiana, looked clear, but booms laid out to catch the oil told a different story.

One strip of booms surrounds the shoreline. The second strip, which follows it like a white ribbon, is meant to absorb as much oil as possible. That strip was turning black from the oil; oil droplets breached the barrier.

“This is stuff that has just very recently started coming to shore. It’s going to keep going certainly as long as blowout keeps going offshore,” said Rick Steiner, a marine conservation specialist who worked on the Exxon Valdez oil spill. “But even if they capped it today, we’ve got 4 [million] to 5 million gallons of this stuff in the Gulf and it’s going to just keep moving back and forth with the currents and the wind.”

Oil sheen is also visible in the Chandeleur Islands to the east, part of the Breton National Wildlife Refuge.

The wetlands are in the farthest reaches of Plaquemines Parish, the first place where the oil has come ashore.

Parish President Billy Nungesser is asking BP to pay for a $250 million coastal protection plan.

Nungesser wants to dredge and build an 80-mile sand berm to protect the wetlands and wildlife. Nungesser has pressed for a coastal protection plan ever since Hurricane Katrina devastated this area, but he says it’s now urgent.

“We could actually see a storm that would put this oil in everybody’s backyard. We should be doing everything physically possible to minimize any chance,” he said. “We should start pumping immediately and take every, every opportunity we got to keep it out of the marsh.”

In other developments Wednesday:

— The White House asked Congress to raise the limits on BP’s liability to cover damage from the spill beyond the $75 million cap now in law. It also wants oil companies to pay more into a federal oil spill cleanup fund.

— BP President Lamar McKay said the company will pay any legitimate claim of damages beyond cleanup costs despite the federal cap.

— On the Gulf Coast, a new containment box — a cylinder called a “top hat” — was placed on the seafloor near the well leak.

Engineers hope to work out ways to avoid the problem that scuttled an earlier effort with a much bigger box before they move the cylinder over the end of the 5,000-foot-long pipe from the well.

— The Minerals Management Service told a government panel of investigators in Kenner, La., that inspections of deep-water-drilling rigs has turned up only “a couple of minor issues.”

NPR’s Peter Overby, Richard Harris and Kathy Lohr contributed to this report, which includes material from The Associated Press