A Generator Step Up (GSU) transformer failed at the Salem River Nuclear Plant during the March 1989 geomagnetic storm. The unit is depicted on the left; some of the burned 22kV primary windings are shown on the right. Though immersed in cooling oil, the windings became hot enough to melt copper, at about 2000 degrees F. John Kappenman, Metatech

Coronal Mass Ejections are mainly charged particles, protons and electrons. When a CME arrives at Earth, the charged protons and electrons come under the influence of the Earth’s own magnetic field, the magnetosphere. Charged particles spin around the lines of magnetic force that comprise the magnetosphere, which diverts most of CME harmlessly around the planet, keeping Earth’s surface tranquil.

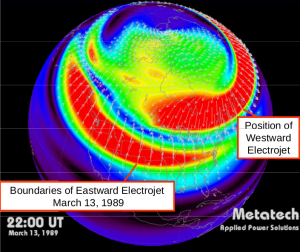

If the ejection is large enough, however, it can distort the shape of the magnetosphere, occasionally causing magnetic flux lines to snap and reconnect. When this happens, charged particles leak in and follow the magnetosphere’s flux lines down to the Earth’s ionosphere. There, they strike oxygen and nitrogen molecules and strip them of electrons. These ionized gases glow, giving rise to the ethereal beauty of the auroras around the north and south poles. Unfortunately, these excess charged particles also produce immense electrojets.